A trip down memory (footprint) lane [Download for the original TextAnalysisTool, circa 2001]

As you might guess from the name, TextAnalysisTool.NET (introductory blog post, related links) was not the first version of the tool. The original implementation was written in C, compiled for x86, slightly less capable, and named simply TextAnalysisTool. I got an email asking for a download link recently, so I dug up a copy and am posting it for anyone who's interested.

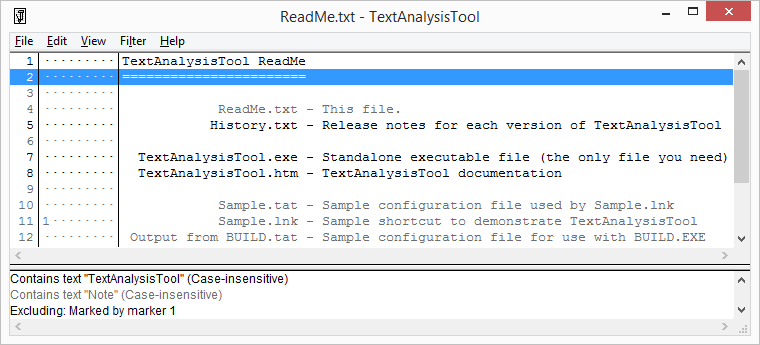

The UI should be very familiar to TextAnalysisTool.NET users:

The behavior is mostly the same as well (though the different hot key for "add filter" trips me up pretty consistently).

A few notes:

- The code is over 13 years old

- So I'm not taking feature requests :)

- But it runs on vintage operating systems (seriously, this is before Windows XP)

- And it also runs great on Windows 8.1 (yay backward compatibility!)

- It supports:

- Text filters

- Regular expressions

- Markers

- Find

- Go to

- Reload

- Copy/paste

- Saved configurations

- Multi-threading

- But does not support:

Because it uses ASCII-encoding for strings (vs. .NET's Unicode representation), you can reasonably expect loading a text file in TextAnalysisTool to use about half as much memory as it does in TextAnalysisTool.NET. However, as a 32-bit application, TextAnalysisTool is limited to the standard 2GB virtual address space of 32-bit processes on Windows (even on a 64-bit OS). On the other hand, TextAnalysisTool.NET is an architecture-neutral application and can use the full 64-bit virtual address space on a 64-bit OS. There may be rare machine configurations where the physical/virtual memory situation is such that older TextAnalysisTool can load a file newer TextAnalysisTool.NET can't - so if you're stuck, give it a try!

Aside: If you're really adventurous, you can try using

EditBinto set the /LARGEADDRESSAWARE option onTextAnalysisTool.exeto get access to more virtual address space on a 64-bit OS or via /3GB on a 32-bit OS. But be warned that you're well into "undefined behavior" territory because I don't think that switch even existed when I wrote TextAnalysisTool. I've tried it briefly and things seem to work - but this is definitely sketchy. :)

Writing the original TextAnalysisTool was a lot of fun and contributed significantly to a library of C utility functions I used at the time called ToolBox.

It also provided an excellent conceptual foundation upon which to build TextAnalysisTool.NET in addition to good lessons about how to approach the problem space.

If I ever get around to writing a third version (TextAnalysisTool.WPF? TextAnalysisTool.Next?), it will take inspiration from both projects - and handle absurdly-large files.

So if you're curious to try a piece of antique software, click here to download the original TextAnalysisTool.

But for everything else, you should probably click here to download the newer TextAnalysisTool.NET.